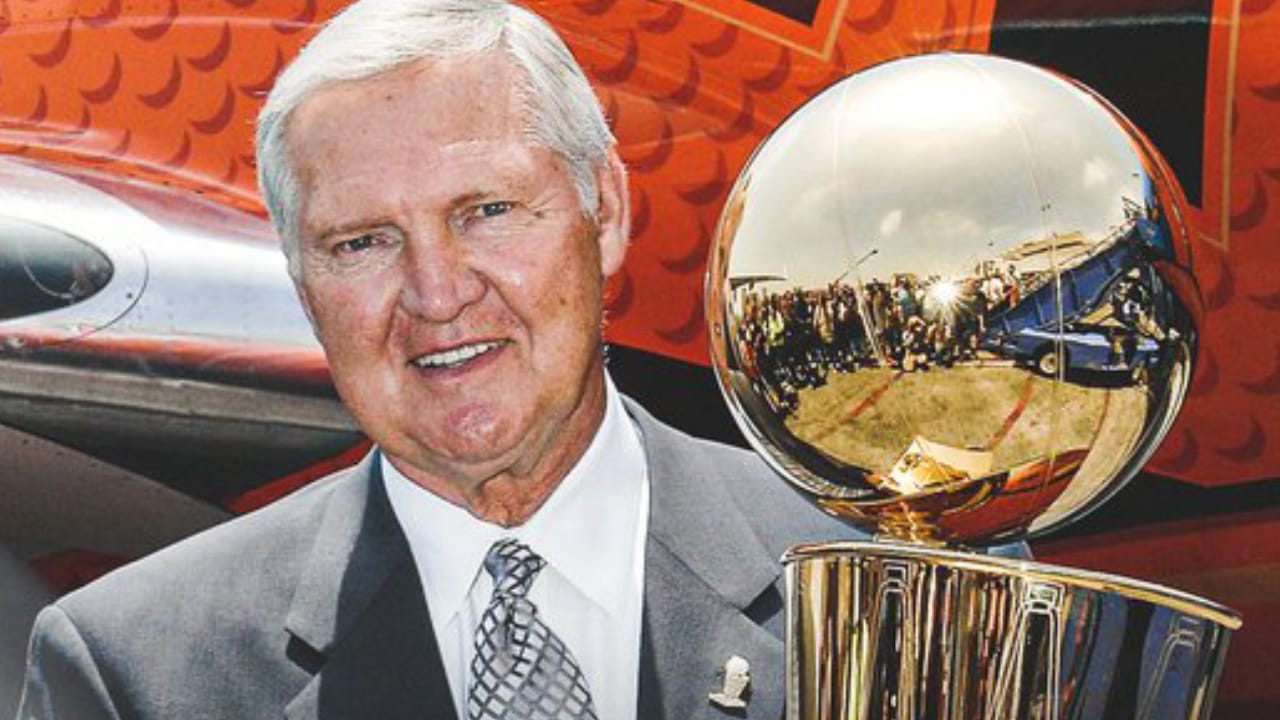

Jerry West and the Weight of Being the Brand Identity

The NBA adopted Mr. Clutch as its symbol because he was such a pivotal character in its history, yet the Hall of Famer was always under pressure to live up to the high standards of perfection.

When I was a young, somewhat bashful, maybe overachieving rookie beat reporter assigned to cover the Lakers for the L.A. Daily News in the summer of 1997, I got to know Jerry West. I was familiar with his background, the titles he had won and lost, the game-winning shots he had made, and the competitors he had built. However, it wasn’t until three summers later that I believe I truly knew the man.

On June 20, 2000, confetti in the colours of purple and gold fluttered about them as Kobe Bryant jumped into Shaquille O’Neal’s arms to celebrate their first NBA title. Twelve years had passed since the franchise had flown a flag. It has been four years since West risked everything to bring the two stars to Los Angeles. His dream of a Lakers comeback was finally coming true. The entire city was ecstatic, joyful, and glowing. Everyone aside from the architect who enabled it all.

I discovered West seated at his desk in his poorly lighted office at the Lakers headquarters. He gave me a warm welcome and consented to respond to a few queries. Obviously, I started up by asking, “Did you enjoy the night?”

He answered firmly, “No, I didn’t. I didn’t follow along.

West didn’t even show up. He had driven around Los Angeles throughout the Game 6 championship game while receiving phone updates. The idea of witnessing in person seemed too burdensome and distressing. He promised to watch the entire series on tape at some point. Over the course of the following twenty minutes, West would mention numerous people by name, including the team’s scouts, Phil Jackson, Shaq and Kobe, the fans, owner Jerry Buss, and even the fans (since, he claimed, they don’t receive enough credit). He didn’t appear content, though. Thus, I persisted once more: How about you? After everything you’ve gone through—all the uncertainty, criticism, and second-guessing—is there any sense of satisfaction?

“Not for me,” he uttered.

Up until then, I saw West as a basketball genius, a living legend, the epitome of Lakers greatness, the uncommon superstar player who went on to become a superstar executive, and someone who was well-liked and revered by all. Mr. Clutch was who he was. He was the NBA’s official emblem, despite the league’s long-standing denials to the contrary. I was aware that he could be fervent, frightening, giving, considerate, sympathetic, chatty, irascible, defensive, and peculiarly insecure at times. But until then, I never really felt the weight of being Jerry West.

Compared to 99 percent of the players, coaches, and executives who have ever played in the NBA, West, who passed away on Wednesday at the age of 86, had greater success. The most difficult element, though, seemed to be enjoying it. No amount of triumphs, titles, or free-agent takeovers would ever satisfy him. The criticism was louder than the appreciation that he heard. It seemed as though he could never reach the level of perfection needed to be the Logo. It seems as though the heartache he had throughout his playing career—one championship versus eight losses in the Finals—left him so damaged that he was always prepared for the worst.

In other words, no, West finally lost the will to be around during the 2000 Finals and could not stand to see any of them in person.

West would depart the Lakers two months after the team won the championship, with no formal farewell, press conference, or explanation provided. However, as Chick Hearn, a Lakers broadcaster and close friend, would later observe, “He feels the pressures are tearing him down physically as well as mentally.” We’d hear that he didn’t feel valued enough. He was reportedly furious that Jackson was seeing Buss’s daughter Jeanie, a team executive at the time. We would learn later that she had a cardiac condition.

West embodied the tormented genius; he was a fiercely competitive and compulsive perfectionist whose own unrealistic standards seemed to cast a shadow over every accomplishment. We were familiar with the fundamentals: As a player, he reached nine Finals but won only one championship (in 1972). The only man to win MVP of the Finals while the team lost (in 1969). twelve games (10 first team) for the All-NBA squad. five players chosen for the defensive all-star team. A title that scores points. A title that helps. a spot on the 35th anniversary team of the NBA. with the group commemorating 50 years. as well as the 75th. And that only applied to the player.

As an executive, West oversaw the Showtime period before assembling Shaq and Kobe to form a new dynasty. His fingerprints are on every one of those banners, even though he left before they could win their second and third titles. After bringing the struggling Memphis Grizzlies back to life, he would play a crucial role in the background as the Golden State Warriors dynasty was being built. He is among the best team executives in sports history. It was difficult to determine how much West actually loved any of it, but it’s safe to say he took a certain delight in it all.

Not that West didn’t enjoy the game itself, mind you. The man was the epitome of a gym rat, participating in NBA summer leagues and predraft training far into his eighties. Over the past 20 years, he has been a quiet confidant to scores of young superstars, many of whom never played for any of the teams he worked with. Opponents may label it as tampering. However, it was the stars that pursued West. And West always felt that he owed it to the game and the generations who came after him to offer any advice he could.

He was equally ready to answer calls from journalists who wanted to hear his thoughts and advice as well as occasionally just to discuss the newest rumours. In 1997, West informed me that he would never talk about anything off the record. Informally? West was a gloriously honest truth-teller and an incorrigible gossip. If he thought a supposed celebrity was overrated, he’d tell you right away—and he was generally correct. He would chastise you for calling a player “great,” claiming the term is overused (and he was right about that, too).

One time, while West was in charge of the Grizzlies, he left a long, foul-mouthed voicemail for a beat writer. He gleefully concluded by stating, “You can call me back in the office, tomorrow.” Goodbye. Ron Tillery, a reporter for The Commercial Appeal who covered the Grizzlies, described him as “incredibly sweet.” Tillery stated that even towards the end, the two continued to speak at least twice a year.

The point is that West was incredibly pleased and passionate about the league he would help to develop, not that he was purposefully cruel or threatening.

West accepted the Memphis job at a time when the Grizzlies were regarded as one of the worst teams in professional sports because he had such a deep love for the game. He led the Grizz to their first three playoff appearances, which may have helped put that team on the map. However, he took offence when the local media praised such a meek accomplishment.

Long after he left, though, West stayed a Laker for eternity, serving as Kobe’s friend and advisor as well as Shaq’s (separately). During one of his early visits to Memphis, West made care to show me his watch: The time zone remained Pacific.

Disagreements with the Buss family, and Jeanie specifically, likely prevented West from ever returning to the team that shaped his identity (and that he contributed to defining). Rather, he would serve as a consultant for the Warriors, helping to bring in Kevin Durant, and then the Clippers, helping to bring in Kawhi Leonard. The game continued to adapt, but because West accepted the shift, he survived as a basketball sage.

We wouldn’t fully comprehend the depth of his trauma and personal suffering until 2011, when his memoirs West by West: My Charmed, Tormented Life, was published. of the childhood physical abuse he endured at the hands of his father. the terrible loss incurred during the Korean War of a loving elder brother. the lack of wealth. the crippling despondency. After disclosing everything in his book, West spoke candidly about mental health for the last ten years, making a lasting impact that surpassed his on-court accomplishments.

At the Sports Business Classroom, a spinoff of the NBA summer league, in July of last year, West addressed a group of 125 students, saying, “There are things you keep hidden forever, that you don’t want people to know about you.” And so he told them about those things, in a conversation that lasted an hour and was honest, challenging at times, and very emotional. Then, West declared, “I’m flawed because of the things I saw growing up.”

That was the final day I would talk to West or see him. Though not as brash or scary as when I initially met him, he appeared more fragile. I made fun of the comment he’d delivered the day before, stating that, in his day and age, he was a “wolf” on the court, as opposed to the simple “dogs” that some players these days refer to themselves as. West chastised me, saying, “It’s not funny.” “I wasn’t joking.”

West returned to the idea towards the end of his talk with the kids.

“People chuckle at my remarks. It’s the reality,” he declared. “Have wolves ever howled at you? How eerie does that sound? Yes, haunting. .. It’s your thoughts on attending those games. That puppy was going to die, I swear. I was going to earn his respect as a player while also letting him know that I would never back down. My entire life, I have been a wolf. And I had to be in order to survive in my own manner.

Even though West was unable to follow in his footsteps, the world honoured Jerry West for everything he accomplished and stood for throughout the years. Perhaps West never thought he deserved all the accolades. Perhaps his trauma would preclude any public recognition. However, the inner wolf was more aware.